In the 1970s, NASA successfully launched four space probes. They first passed through the Solar System, studying Saturn and its moons, before breaking with the Sun’s gravitational orbit – a difficult feat – leaving the Solar System and entering interstellar space. Each probe carried a message for any intelligent life-forms that they may encounter in other planetary systems.

The task of devising messages that could be understood beyond Earth fell to the cosmologist Carl Sagan (1834–1966). For the first two probes, Sagan and his wife Linda designed etchings of humans waving.

The third probe Voyager 1 (launched in 1977) was more ambitious, this time transporting a golden phonograph into space – a record inscribed with sounds selected by Sagan and which attempted to portray planet Earth.

Sagan collected over a hundred natural sounds: the crack of thunder, waves breaking, the sounds of frogs, whales and elephants. To these he added sounds to reflect human life: laughter, heartbeats, footsteps, the sound of tools, the sound of kissing, and fifty-five modern languages.

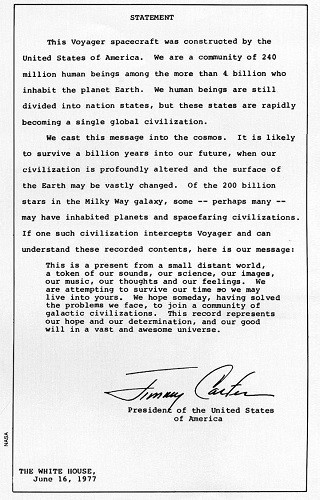

Voyager 1 was a time capsule, a cosmic message in a bottle. Alongside the golden record was a letter from US President Jimmy Carter (b. 1924), who had been elected that same year. Carter is remembered as one of the greenest US presidents, who increased the powers of the Environmental Protection Agency to clean up hazardous waste sites in 1980; and passed laws during his presidency to preserve over 150 million acres of Alaskan wilderness.

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours”

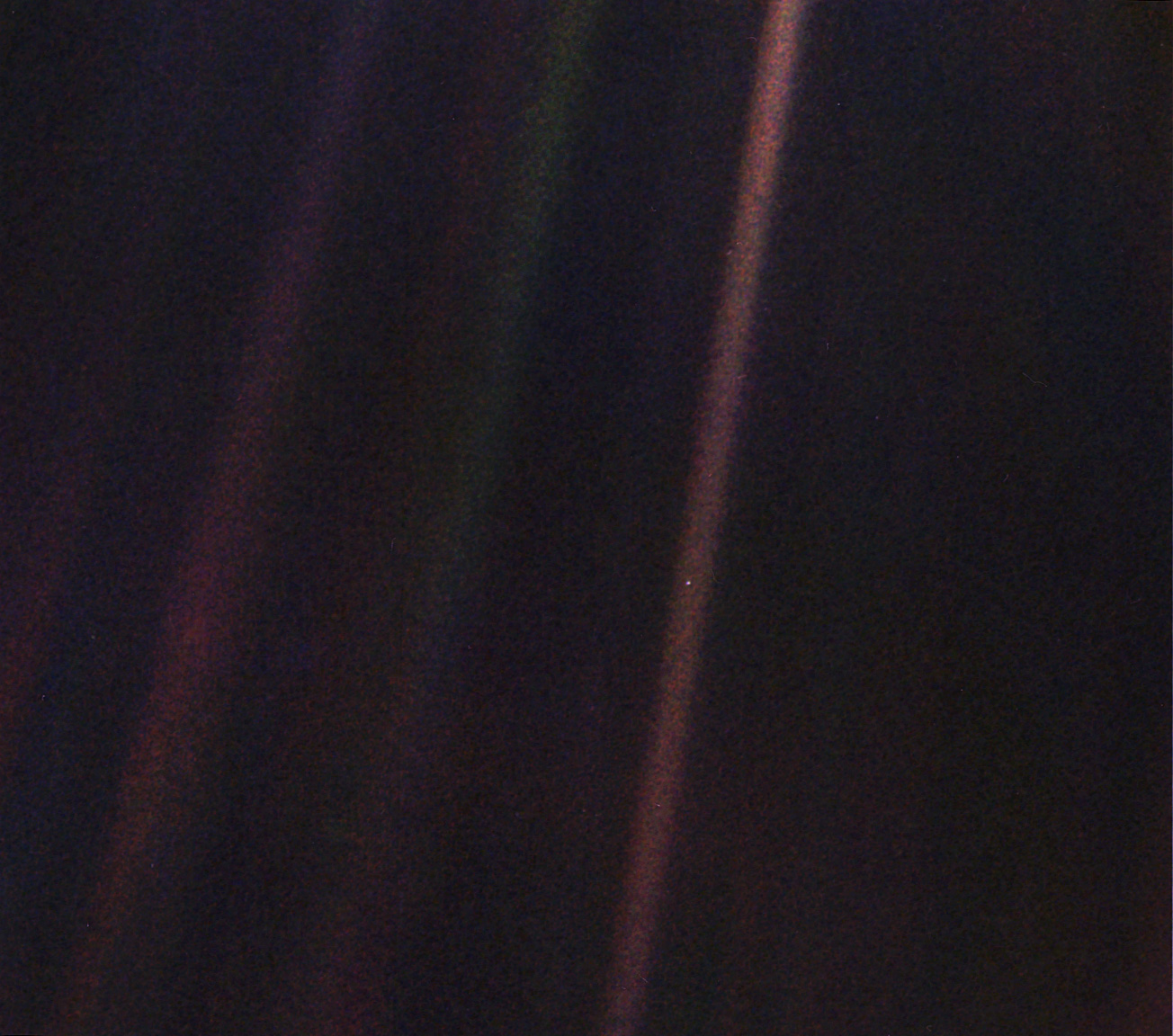

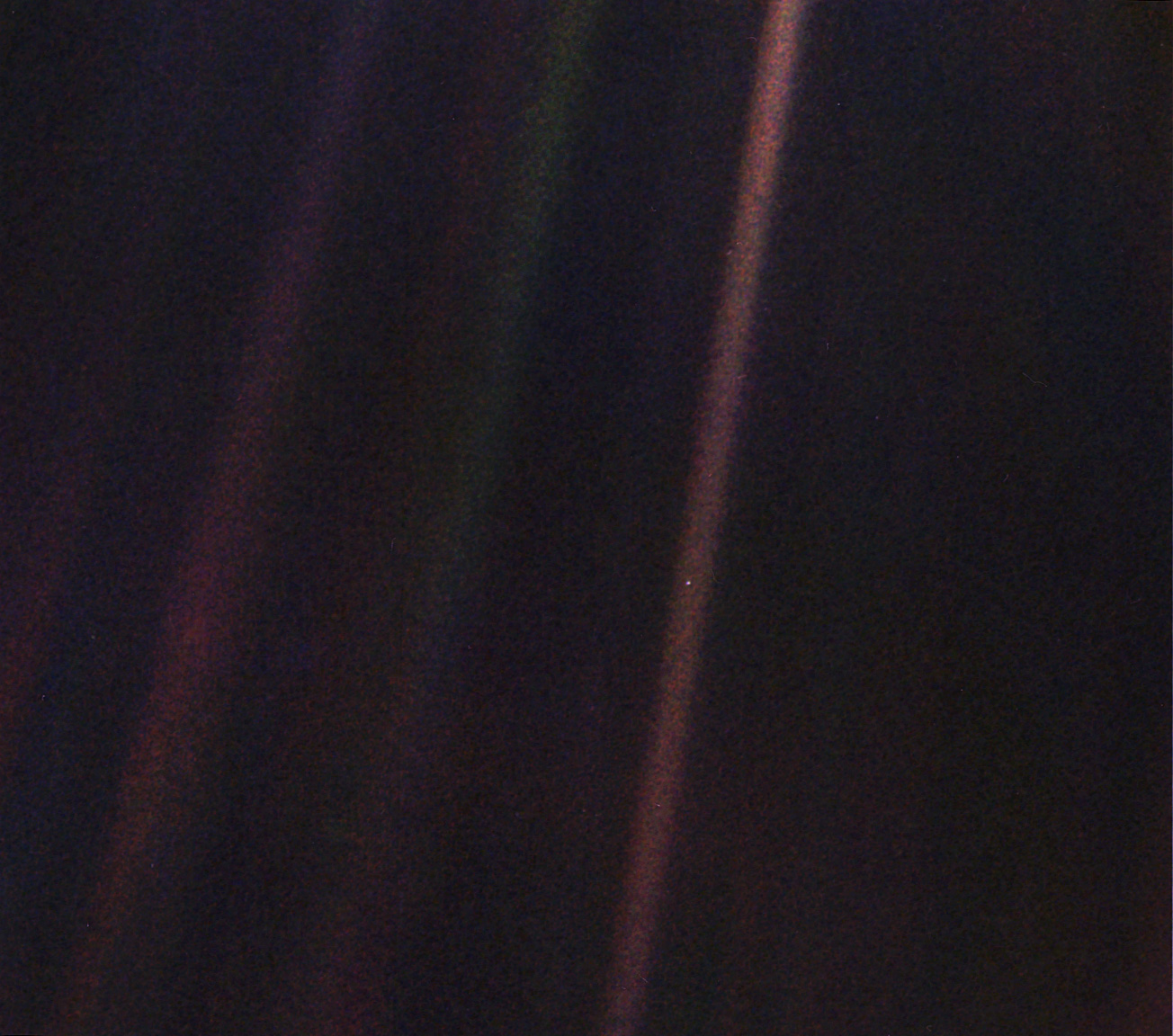

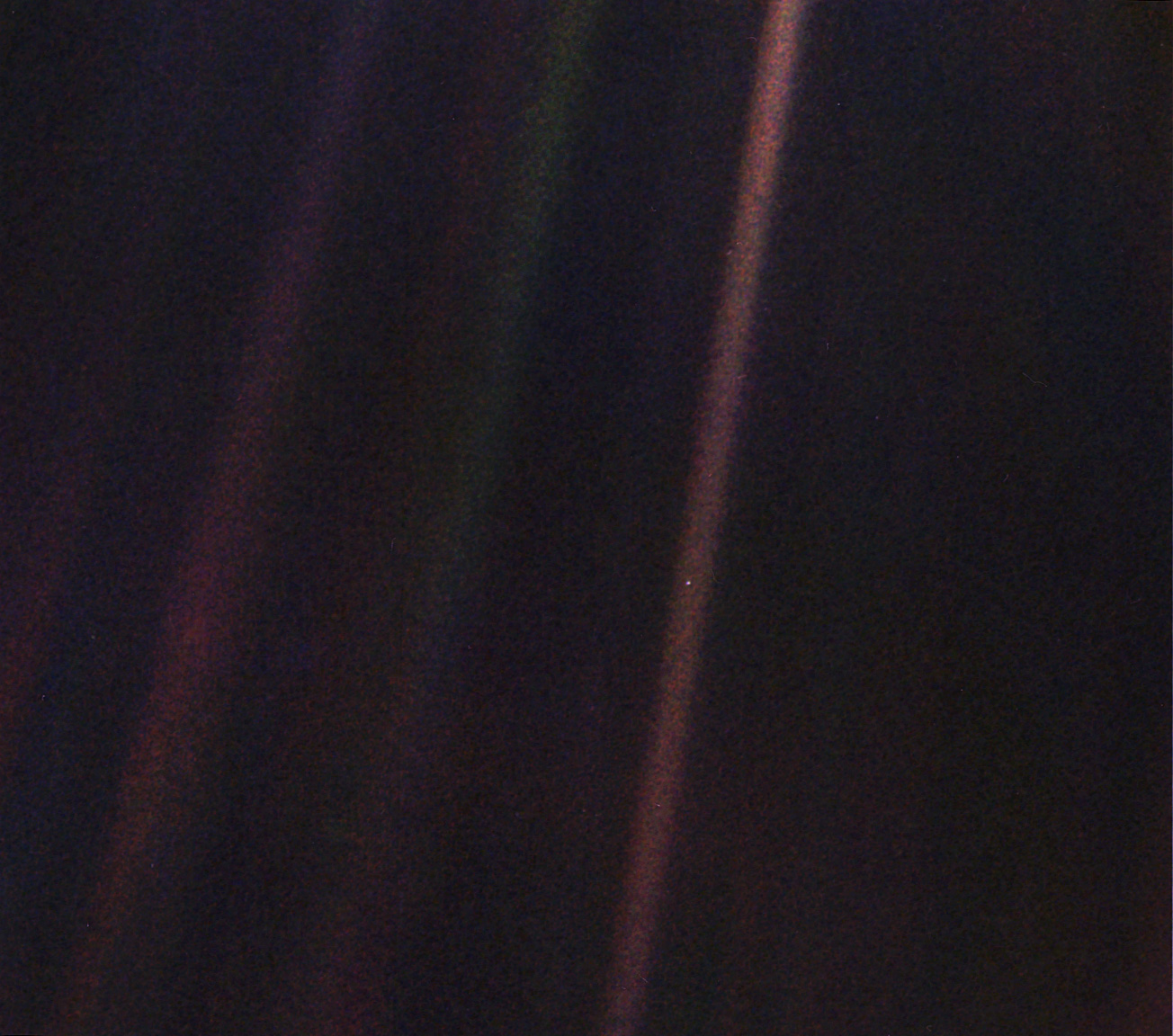

Voyager 1 is a document of the voraciously alive planet we live on. Eighteen years later, the probe would send a portrait of Earth home, taken 6 billion kilometres in the distance. In the photograph, which became known as ‘The Pale Blue Dot’, Earth appears as a watery-blue, living dot amid the vastness of space.

In an age of environmental emergency, the following letters from activists, scientists and writers show what individuals have been doing, across different decades, to protect our living oasis.

Chapter One: Conservation

Human concern for nature dates back millennia. Examining and worrying about the environment was intrinsic to survival, and the endurance of ancient societies was based, in part, on their success in living in alignment with the natural world.

Care and attention to the animal world can be seen in ancient environmental messages, which survive into the present. Some of the oldest nature letters are the Nazca Lines, hundreds of shapes scratched into the Nazca Desert in southern Peru, including seventy zoomorphic signs and plant motifs, which date back to 500 BC. The markings, which show lizards, spiders, herons and hummingbirds, have fascinated anthropologists for decades, some of whom have suggested the

letters invoked the aid of nature, soliciting water for crops.

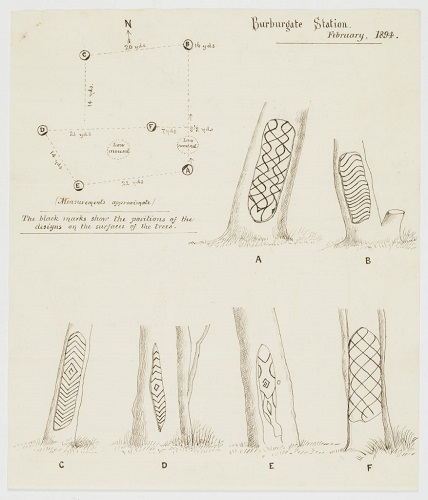

Like the nature they portray, many of the signs of ancient societies have themselves been lost to human expansion, industrialisation and colonialism. A letter from Matthew Thomson reflects a rare attempt to preserve indigenous Australian tree carvings that show a pre-colonial connection to the land.

Other letters argue against the human destruction and domination of nature. In the New World, the wilderness rapidly began to disappear in the nineteenth century, due to the insatiable appetite for timber and a new popular pastime: hunting. By the 1850s, the bison had been almost exterminated, the jaguar had disappeared, and many birds, from the ivory-billed woodpecker to the Carolina parakeet, were almost extinct.

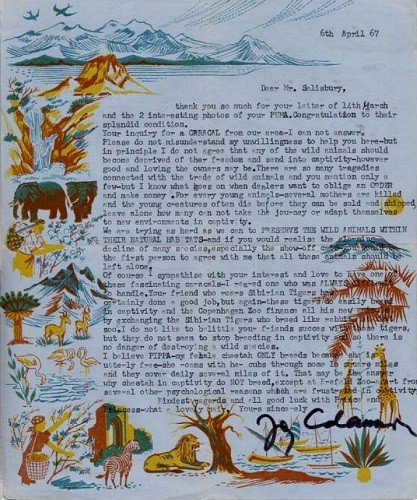

While President Theodore Roosevelt wished to conserve such species, his motives were twofold: both for future prosperity and out of a desire to hunt them. Later, in 1956, it was the shooting of a lioness that led Joy Adamson to devote her life to the conservation of wild cats.

Matthew Thomson to the Royal Anthropological Society of Australasia, 1894

An attempt to conserve, rather than destroy, an ancient connection to the land.

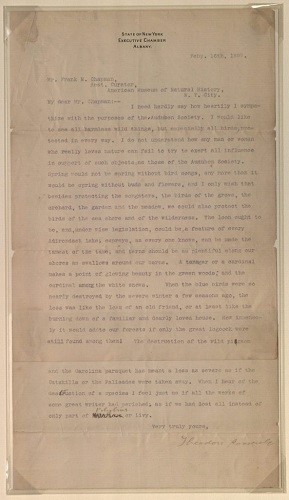

Theodore Roosevelt to Frank Chapman, 1899

Teddy Roosevelt was an avid hunter of big game, yet he is remembered for his conservation policies.

Joy Adamson to Mr Salisbury, 1967

The writer of Born Free argues against keeping animals in captivity.

Chapter Two: Pollution

Rachel Carson opens her seminal book on environmental change Silent Spring (1962) with a fable. “There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings,” she begins, sketching out an American idyll.

But a dark shadow falls over the town, “a strange blight” as she calls it, “crept over the hedges and streams, over the wildflowers and berries and ferns…. mysterious maladies swept the flocks of chickens; the cattle and sheep sickened and died. Everywhere was a shadow of death.” Spring was silent. This is not witchcraft, writes Carson, but the result of chemical spraying – toxic pollution. “The people had done it themselves.”

Pollution means to make dirty. It is almost exclusively a human phenomenon: the

vast majority of pollution is made by man. Aside from natural disasters, like volcanic eruptions, that have fascinated civilisations across history, the advent of pollution as we understand it today is the Industrial Era and the rise of coal.

Compared to oil and gas, coal emits more carbon per unit of energy, leaving traces in the air as soot or, worse, as deadly smog. It was during the Industrial Revolution that the atmosphere became a dumping ground. So thick was London smog in the 1880s that it deprived vegetation of sunlight.

Alongside coal pollution was the problem of mass urbanisation. Flocking to cities

to work in factories, a rising population pushed urban sanitation to breaking point. The population of London rose from 1 million to 3 million over a period of fifty years;

construction could not keep apace.

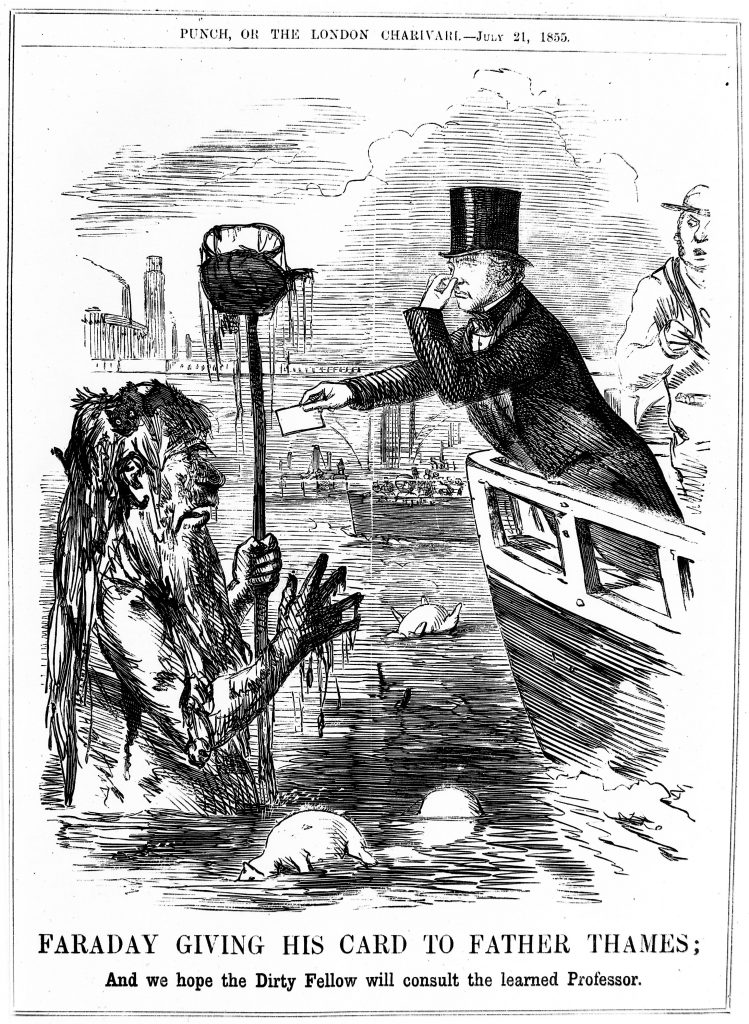

One prominent and visible complication was human sewage. London of the 1850s was not yet a modern city. The city still used hundreds of thousands of Medieval cesspits that leaked gases, caught fire and sometimes exploded. The River Thames itself was an open sewer, with human excretion flushed down a network of wooden pipes. On top of this, slaughterhouses and factored dumped bones and waste into the river, which by the 1850s had reached a peak of revulsion. In one of the letters included below, the Victorian chemist Michael Faraday (1791-1867) describes the polluted Thames in detail.

Since then, pollution has evolved into new forms – pesticides, oil spills, nuclear waste –spelling new dangers for the environment. And individuals continue to write letters – themselves in new, evolving forms.

Michael Faraday to The Times, 1855

The Victorian chemist Michael Faraday warns about pollution in the Thames.

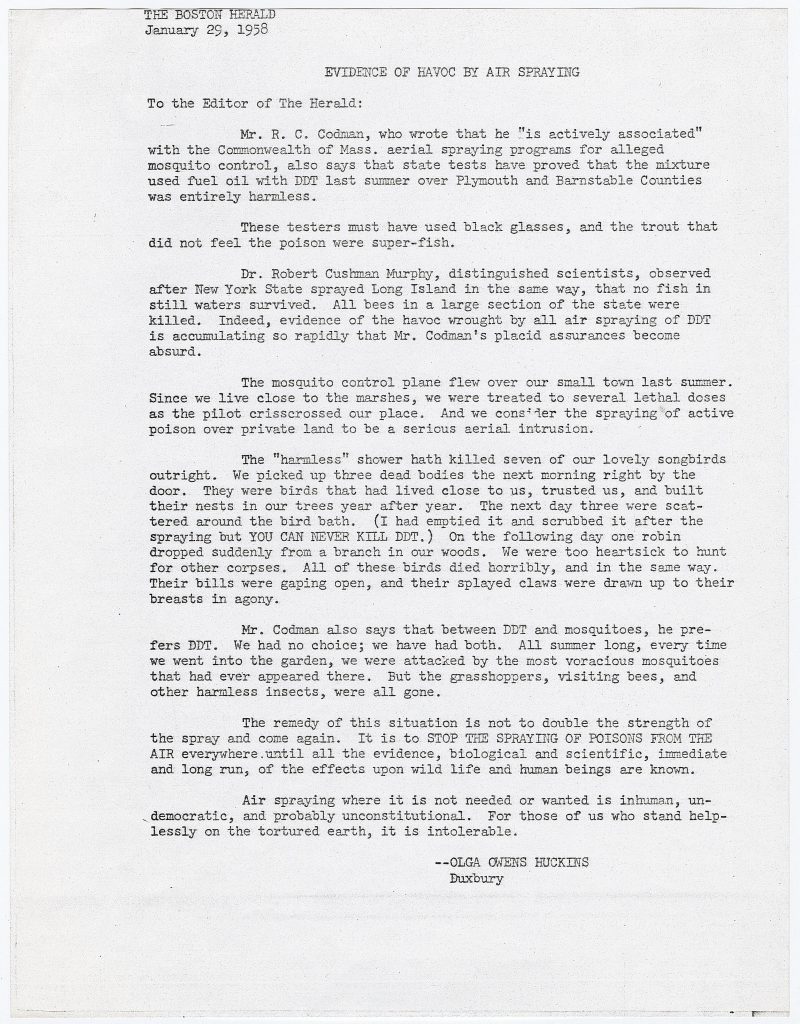

Olga Huckins to The Boston Herald, 1958

DDT and the letter that spurred Rachel Carson to write her seminal investigative book, Silent Spring (1962).

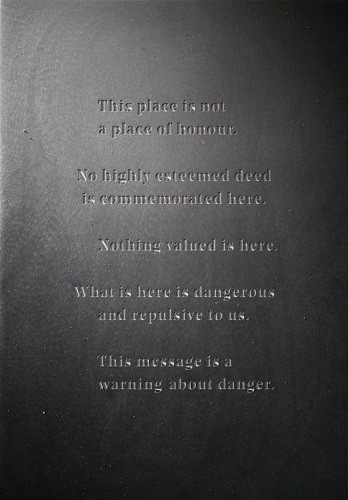

The Futures Panel’s warning to future generations, 1993

A warning set to outlast entire civilisations.

Chapter Three: Action

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) raised public awareness about the inextricable link between pollution and public health. It became a source of inspiration to millions of people, and a rallying point for a new grassroots environmentalism emerging in the 1970s.

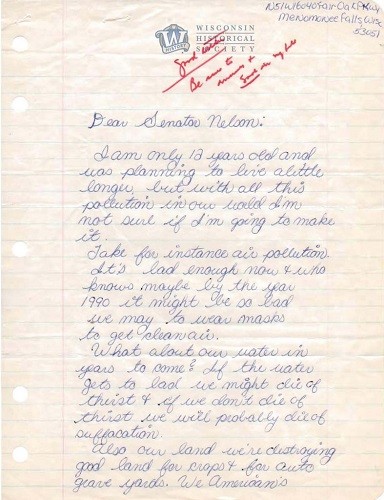

The book inspired one senator, Gaylord Nelson, to announce an environmental awareness week that would later become Earth Day. On 22 April 1970, twenty million people across the US participated in events, which included tree planting and litter picking. The grassroots actions of Earth Day continue to this day, sparking environmental consciousness in generations of children, such as Karen Patnode, who wrote a letter in response.

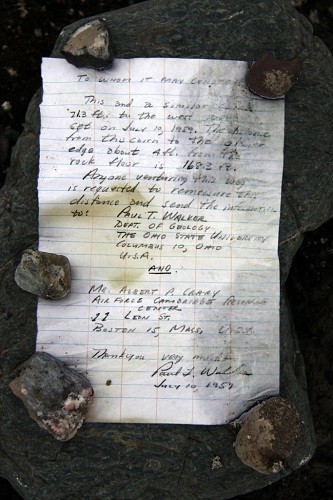

Action takes place in the furthest reaches of the earth, far from any public demonstration. Geologist Paul T. Walker wrote a letter from an island in the Canadian Arctic in 1959, including the distance to a local glacier, before stuffing it in a bottle and hiding it under a pile of rocks. Discovered fifty years later, the message revealed to contemporary scientists just how much the glacier had shrunk, pinpointing the alarming rates of ice retreat, otherwise difficult to prove.

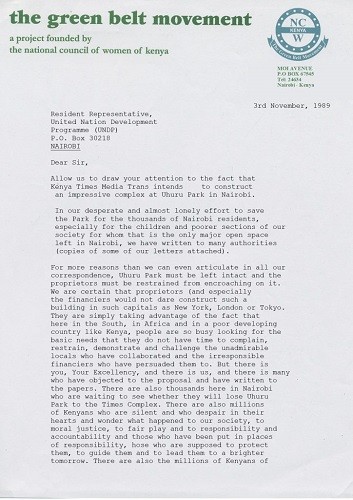

Other prominent campaigns are women-led. In Kenya, a biologist named Wangari Maathai founded the Green Belt Movement in 1977, which trained women in bee-keeping and forestry, and mobilised millions of Kenyans to plant trees. As Maathai’s letter attests, she dispatched endless letters to governments and organisations across her life, campaigning to keep the earth green and liveable for generations to come.

Paul T. Walker’s message in a bottle, 1959

A hidden note reveals the extent of a glacier’s shrinkage over time.

Wangari Maathai to the UN Development Programme,1989

Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai on “the arrogance of those who are promoting destruction”.

Karen Patnode to Senator Gaylord Nelson, Founder of Earth Day, 1992

A concerned 12 year old shares her fears with a US senator.

Chapter Four: The Future

Writing to the Future refers to missives of conservation and prophecy.

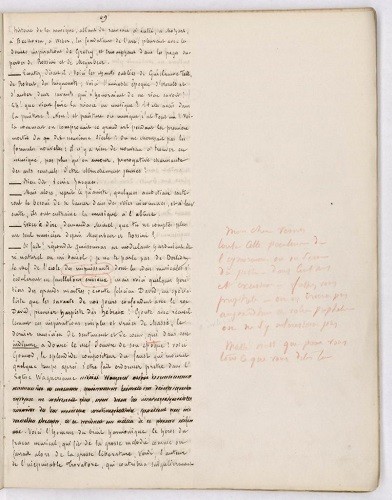

French novelist Jules Verne’s 1863 novel Paris in the Twentieth Century was the latter, sketching a future Paris hit by climate collapse. However his book was rejected by his editor. Pierre-Jules Hetzel despised the manuscript, which he found entirely far-fetched. His notes to Verne, in the margin of the manuscript, are preserved in a French library as an early example of climate change denial.

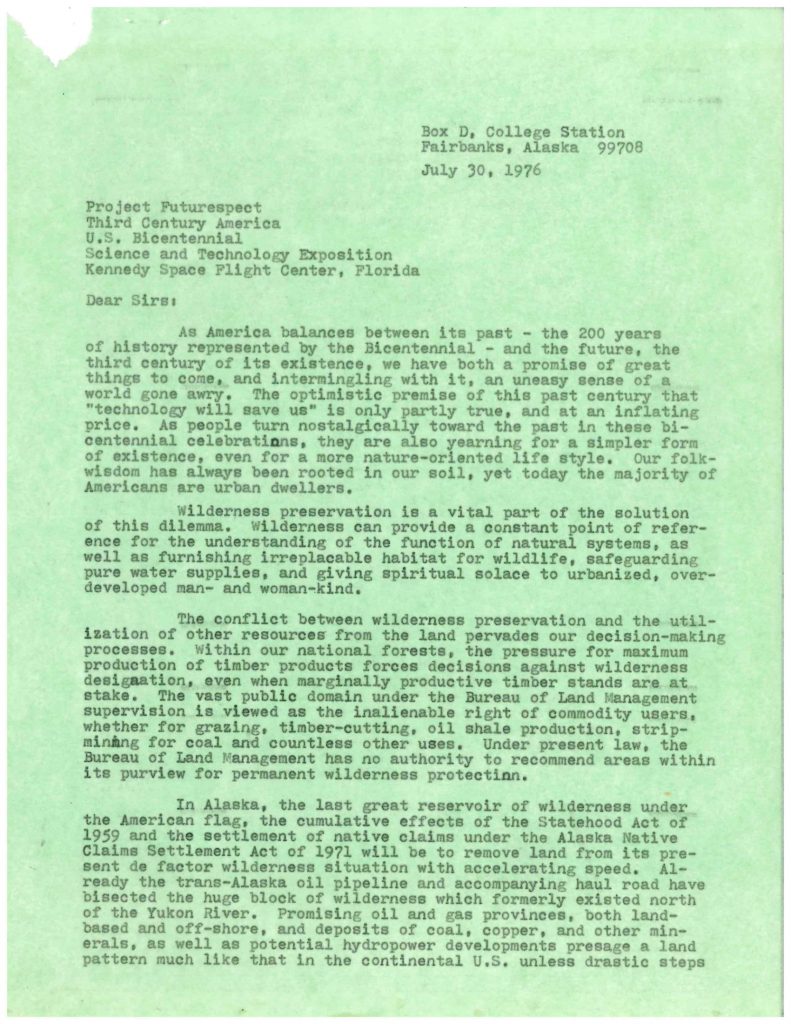

Celia M. Hunter (1919-2001) was an environmental campaigner and pilot, who moved to Alaska in the 1950s and spent her life attempting to protect it. A bill in 1960 protected 9 million acres (out of 420 million), but it was not enough for Hunter. In her letter, included below and written to citizens of the future, she lays out the manifold threats to the Arctic wilderness. Her tireless campaigning paid off; by 1980, a new law protected 19 million acres, its name shifting from “Range” to “Refuge”.

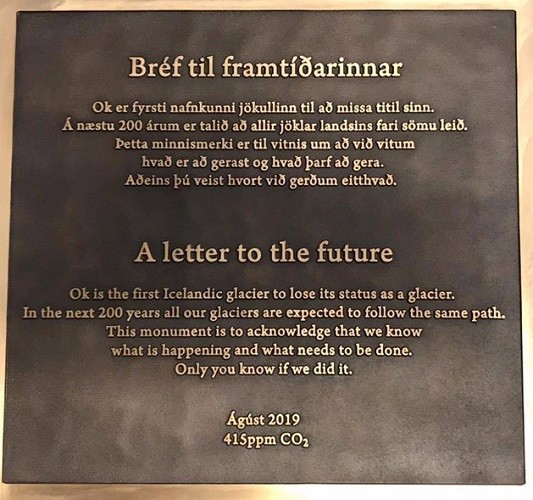

“In the future, glaciers will be an alien phenomenon, rare as a Bengal tiger,”

writes the Icelandic novelist Andri Snær Magnason in On Time and Water (2020).

“Having lived in the time of the white giants, will become swaddled in a fairy-tale glow, like having stroked a dragon or handled the eggs of the great auk.” Magnason helped to write Iceland’s own letter to the future, despairing at the first death of a major glacier and setting a challenge for future generations.

Pierre-Jules Hetzel to Jules Verne, 1863

An incensed editor fails to recognise a writer’s prophecy for the future.

Celia M. Hunter, for the National Science and Technology Bicentennial, 1976

Celia M. Hunter lays out the manifold threats to the Arctic wilderness.

Iceland’s letter to the future, written by Andri Snær Magnason, 2019

The death of a glacier sparks a warning call to future generations.