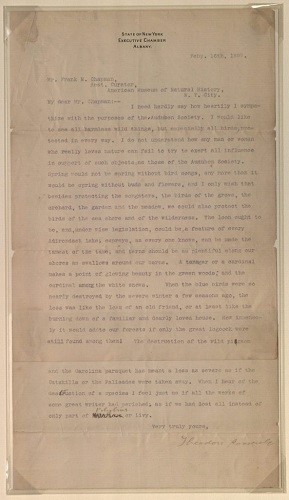

Feb, 16th, 1899,

Frank M. Chapman,

Asst. Curator

American Museum of Natural History

N.Y. City.

My dear Mr. Chapman:–

I need hardly say how heartily I sympathize with the purposes of the Audubon Society. I would like to see all harmless wild things, but especially all birds, protected in every way. I do not understand how any man or woman who really loves nature can fail to try to exert all influence in support of such objects as those of the Audubon Society.

… Spring would not be spring without bird songs, any more than it would be spring without buds and flowers, and I only wish that besides protecting the songsters, the birds of the grove, the orchard, the garden and the meadow, we could also protect the birds of the sea shore and of the wilderness The Loon ought to be, and, under wise legislation, could be a feature of every Adirondack lake; Ospreys, as everyone knows, can be made the tamest of the tame, and Terns should be as plentiful along our shores as Swallows around our barns. A Tanager or a Cardinal makes a point of glowing beauty in the green woods, and the Cardinal among the white snows.

… When the Bluebirds were so nearly destroyed by the severe winter a few seasons ago, the loss was like the loss of an old friend, or at least like the burning down of a familiar and dearly loved house. How immensely it would add to our forests if only the great Logcock were still found among them!

The destruction of the Wild Pigeon and the Carolina Paroquet has meant a loss as severe as if the Catskills or the Palisades were taken away. When I hear of the destruction of a species I feel just as if all the works of some great writer had perished; as if we had lost all instead of only part of Polybius or Livy.

Very truly yours,

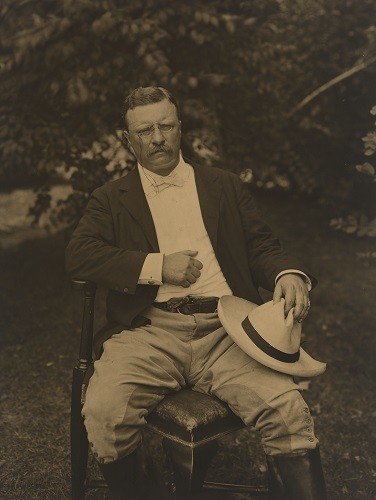

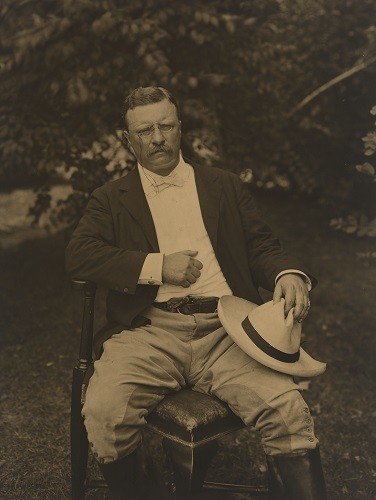

Theodore Roosevelt

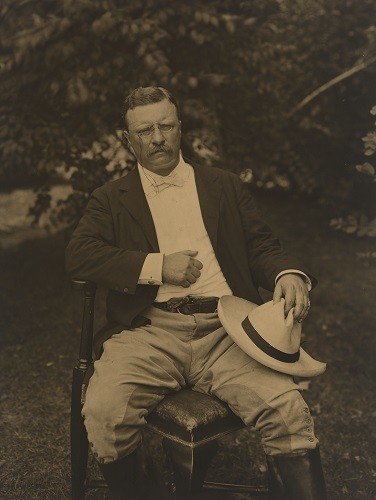

In 1899, Roosevelt had just been appointed Governor of New York. Frank Chapman (1864-1945), who worked at the American Museum of Natural History in Central Park, had recently helped to found a regional branch of the Audubon Society, a wildlife organisation named after the great American bird painter JJ Audubon.

In 1899, Roosevelt had just been appointed Governor of New York. Frank Chapman (1864-1945), who worked at the American Museum of Natural History in Central Park, had recently helped to found a regional branch of the Audubon Society, a wildlife organisation named after the great American bird painter JJ Audubon.

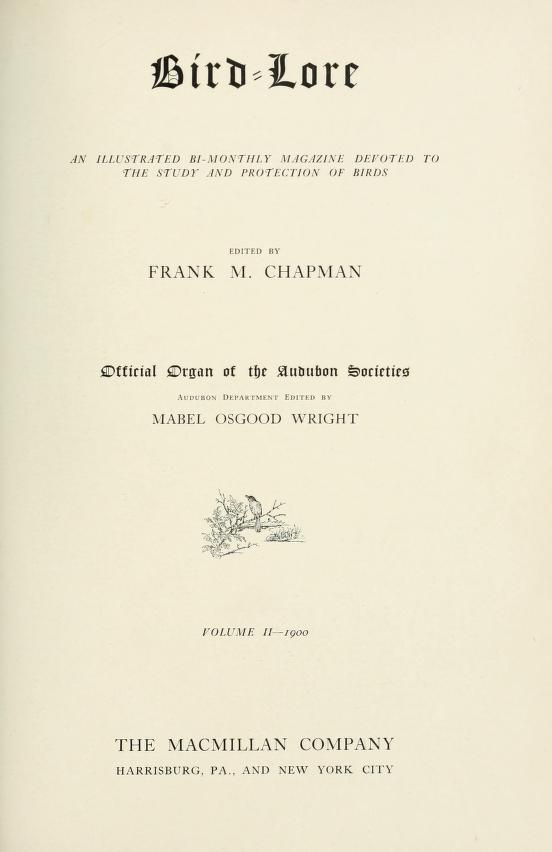

Chapman himself was deeply concerned about the decline of bird populations across America, and that year also founded a new magazine, Bird-Lore, for Audubon Society members, in which he introduced the idea of a Christmas Bird Count. Instead of seasonally shooting birds, Chapman proposed volunteers would go out and count the birds in a new kind of hunt: a census.

Roosevelt’s letter to Chapman sets out his desire to protect birds and “all harmless wild things”. But Roosevelt was also an avid hunter of bear and elk, and desire for national parks was double sided: he hoped to restock the wild places and keep big game alive for future hunters.

Roosevelt’s letter to Chapman sets out his desire to protect birds and “all harmless wild things”. But Roosevelt was also an avid hunter of bear and elk, and desire for national parks was double sided: he hoped to restock the wild places and keep big game alive for future hunters.

Roosevelt’s vision, in line with wilderness thinking, of reserves unmarred by mankind also disregarded First Nation life, which he considered riffraff that needed to be cleared away, like invasive species.

Three years after writing this letter, Roosevelt would become President of the US (1901-09), following the assassination of William McKinley. As this letter indicates, Roosevelt made conservation a priority of his administration, establishing many new national parks, forests, and 51 bird reserves.

Three years after writing this letter, Roosevelt would become President of the US (1901-09), following the assassination of William McKinley. As this letter indicates, Roosevelt made conservation a priority of his administration, establishing many new national parks, forests, and 51 bird reserves.

Chapman was understandably pleased with this letter in praise of the Audubon Society, and it was published in the second ever issue of Bird-Lore in 1899.