Nuclear waste remains dangerous to humans across millennia. Most countries with nuclear power plants keep their spent fuel in containers in temporary facilities. In 1994, Finland became to first only country to create a deep geological disposal unit on the island of Olkiluoto, called “Onkalo” (Finnish for “cavity”) which stores nuclear waste 420 metres below surface, aiming that it will remain there for 100,000 years. The US followed in 1999, when the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) was finally completed, its own contentious deep repository for the disposal of radioactive waste in New Mexico.

Crucially, any repositories must be labelled so that archaeologists of the future are to understand they are not sites to be excavated. This is more difficult that it might sound: nineteenth century archaeologists who excavated the private tombs of Ancient Egypt encountered warnings, promised curses – but this did not deter activities. The first attempts to take on this question date back to the late 1980s in the US.

In 1993, the Department of Energy commissioned a group of sociologists, science-fiction writers, futurists and artists to help create a design for a long-term warning to place on top of the New Mexico WIPP, working with the nearby Sandia National Laboratories. At the Futures Panel, some members of proposed pictograms to show the landscape was ominous and non-natural, from jagged lightning bolts, or an image of Edvard Munch’s painting of 1893, The Scream.

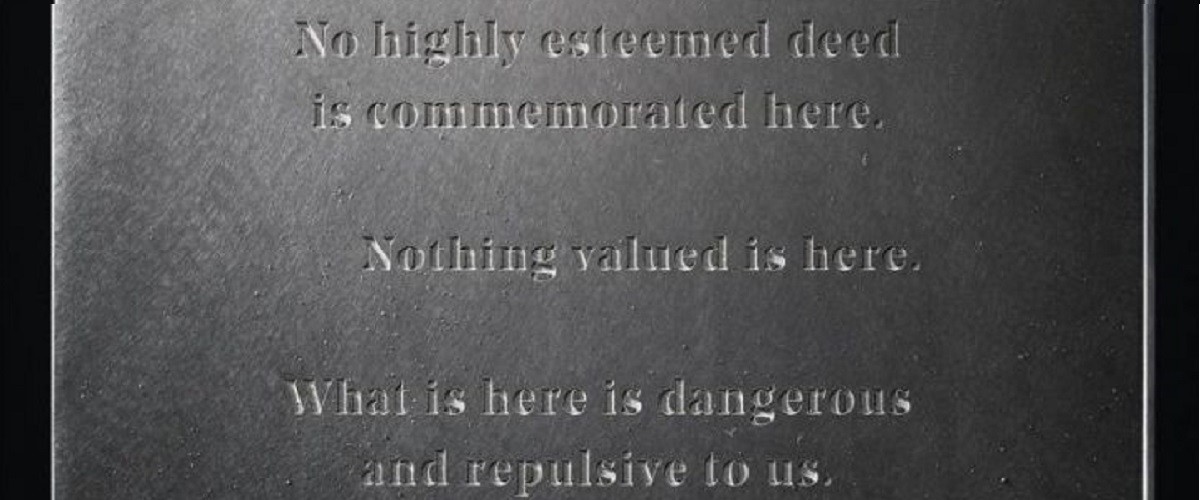

Eventually the group came up with a recommendation: to build a “message” wall in concrete, lead or granite on top of the site, with a chiselled message, in seven languages from local Navajo to Chinese, on a slab. The proposed message was intended to instil fear in those who could understand it.

The WIPP is currently due to be sealed in 2038. While the plans for marking the site remain under development, the current design is for a chamber above the entrance, built from granite and concrete, which will carry a message cut into stone.