7 July, 1855

Sir,—

I traversed this day by steamboat the space between London and Hungerford Bridges, between half-past one and two o’clock. It was low water, and I think the tide must have been near the turn. The appearance and smell of the water forced themselves at once on my attention. The whole of the river was an opaque pale brown fluid. In order to test the degree of opacity, I tore up some white cards into pieces, and then moistened them, so as to make them sink easily below the surface, and then dropped some of these pieces into the water at every pier the boat came to. Before they had sunk an inch below the surface they were undistinguishable, though the sun shone brightly at the time, and when the pieces fell edgeways the lower part was hidden from sight before the upper part was under water…

… This happened at St. Paul’s Wharf, Blackfriars Bridge, Temple Wharf, Southwark Bridge, and Hungerford, and I have no doubt would have occurred further up and down the river. Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface even in water of this kind. The smell was very bad, and common to the whole of the water. It was the same as that which now comes up from the gully holes in the streets. The whole river was for the time a real sewer. Having just returned from the country air, I was perhaps more affected by it than others; but I do not think that I could have gone on to Lambeth or Chelsea, and I was glad to enter the streets for an atmosphere which, except near the sink-holes, I found much sweeter than on the river.

… I have thought it a duty to record these facts, that they may be brought to the attention of those who exercise power, or have responsibility in relation to the condition of our river. There is nothing figurative in the words I have employed, or any approach to exaggeration. They are the simple truth. If there be sufficient authority to remove a putrescent pond from the neighbourhood of a few simple dwellings, surely the river which flows for so many miles through London ought not to be allowed to become a fermenting sewer. The condition in which I saw the Thames may perhaps be considered as exceptional, but it ought to be an impossible state; instead of which, I fear it is rapidly becoming the general condition. If we neglect this subject, we cannot expect to do so with impunity; nor ought we to be surprised if, ere many years are over, a season give us sad proof of the folly of our carelessness.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

M. Faraday.

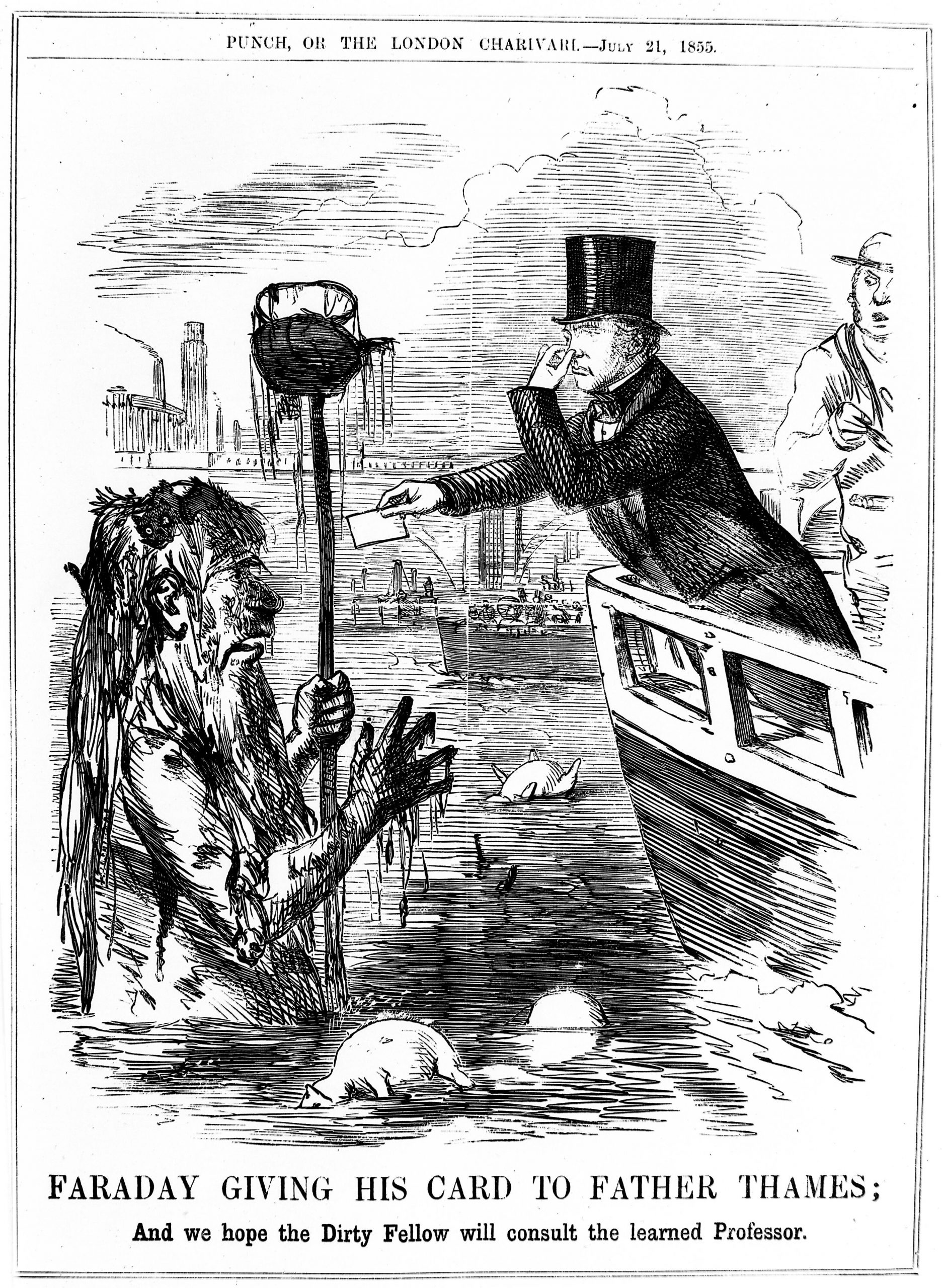

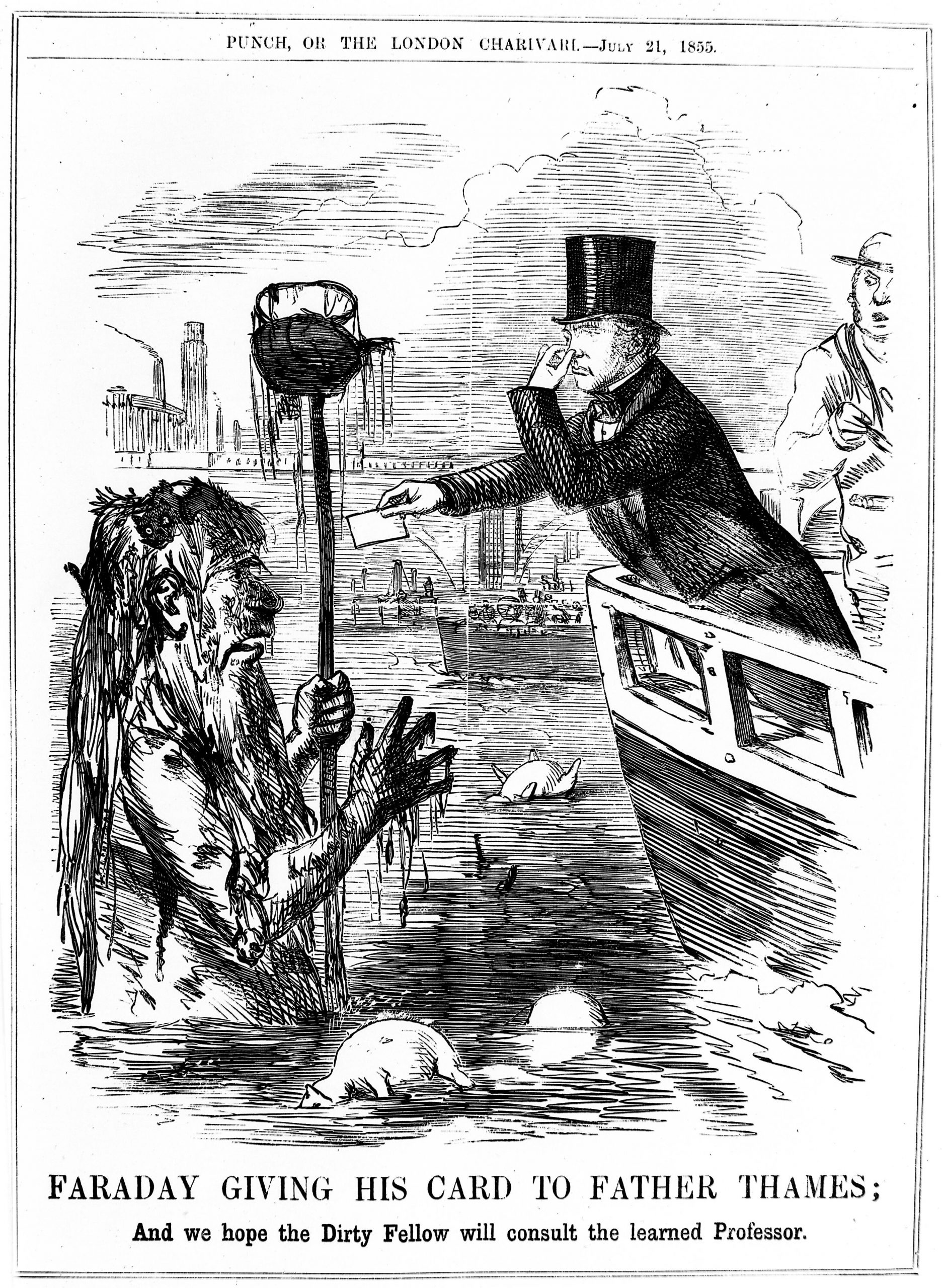

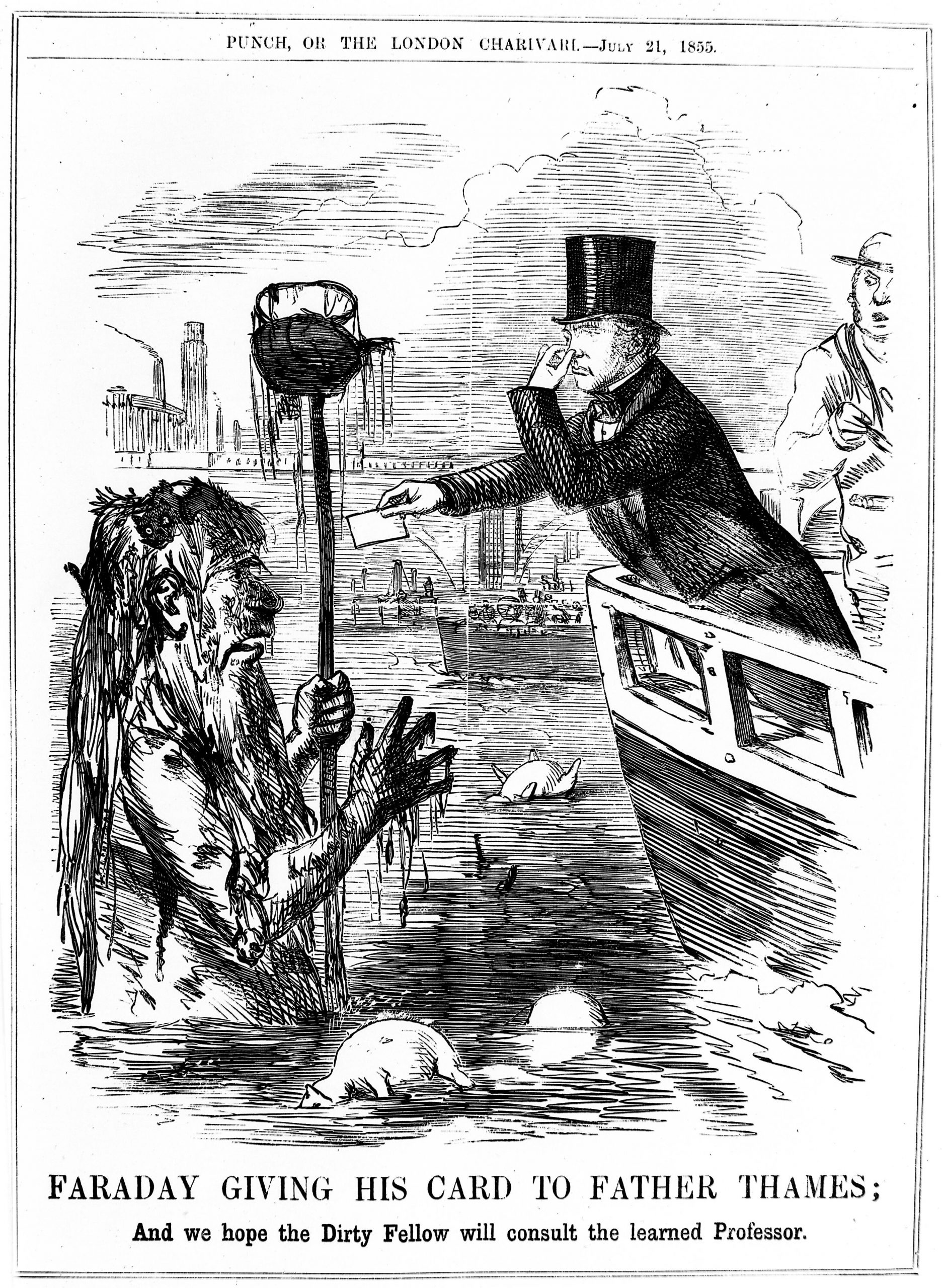

The English electrochemist and early environmental scientist Michael Faraday (1791– 1867) wrote a letter to The Times in 1855, complaining of the severe pollution to the River Thames. Faraday observed increasing amounts of raw sewage and waste dumped into the river.

Three years later, in August, the hot weather exacerbated the sewage in what is remembered as the Great Stink. So strong and noxious were the fumes, they were believed to transmit diseases, and there were three cholera outbreaks that year. “Dirty Father Thames”, went one popular song. “Filthy river, filthy river… Into thee the City throws.”