Discover famous historical letters with the Letters for the Ages series

Get a glimpse into the intimate thoughts of history’s artists, scientists, prisoners, philosophers, and public figures through Of Lost Time’s Letters for the Ages series.

Letters for the Ages is a series of eclectic anthologies, each comprised of around 100 outstanding letters written throughout history, and united by an overarching theme. The resulting volumes burst with the charm and quirkiness of the individuals whose words are brought to life – their stories told, often for the first time, in their own voice.

Learn more about our Letters for the Ages books below and order your copies now to dive into the past!

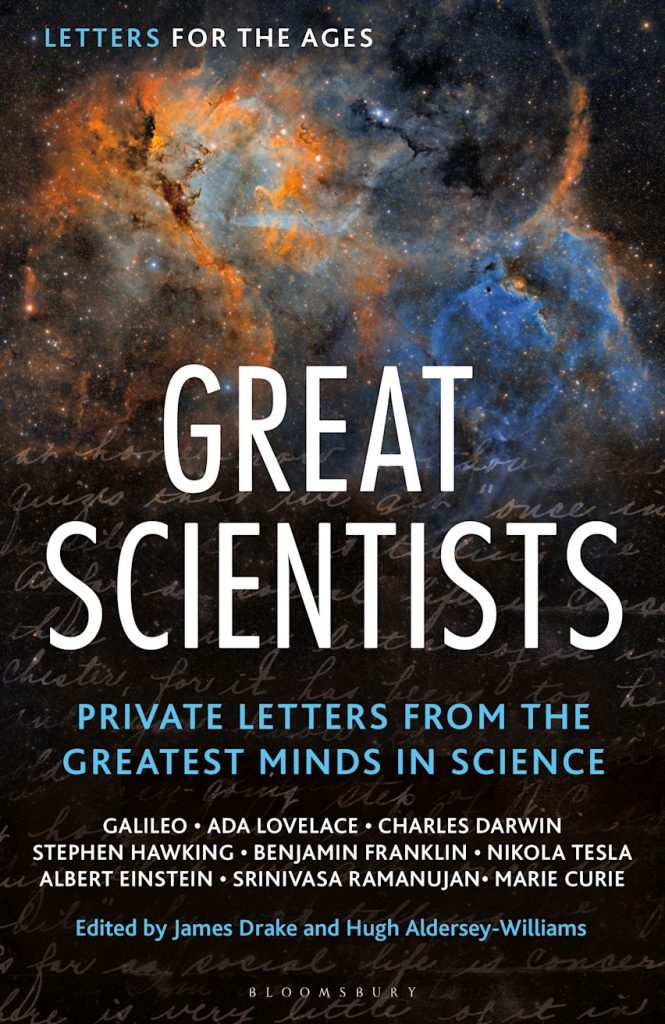

Great Scientists

A collection of the most fascinating letters by the world’s greatest scientists.

‘Most people say that it is the intellect which makes a great scientist. They are wrong: it is character’ – Albert Einstein

Scientists are not often remembered for their character, but rather for the enduring impact of their ideas, inventions, and discoveries. Letters for the Ages: The Great Scientists delves beyond the known historical facts and narratives to uncover the personal writings of some of history’s greatest thinkers and innovators, drawing together private and intimate letters from across almost 500 years of scientific history.

This collection illuminates the individuals behind humanity’s greatest ideas and inventions – from the vaccine to the telephone, the engine to the X-ray – and those responsible for broadening our understanding of our world and the universe beyond. Each letter provides us with an opportunity for exploration and empathy – each a new chance to understand the desires to create, discover and improve held at the core of our humanity.

Immerse yourself in the words of some of history’s greatest scientific minds, including Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin, Marie Curie, Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, Galileo Galilei, Alan Turing and Stephen Hawking amongst many others.

Available in hardback and e-book formats.

Links to buy

Bloomsbury

Waterstones

Amazon

Bookshop.org

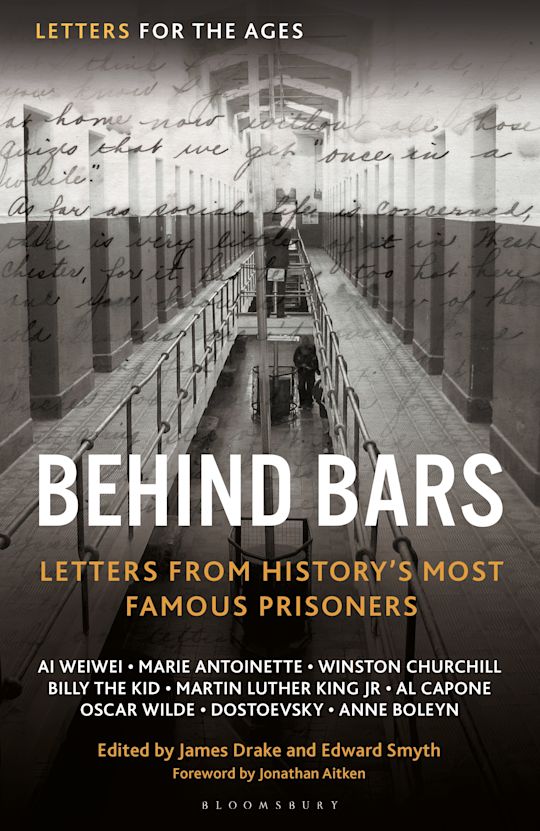

Behind Bars

Letters for the Ages Behind Bars is a history of imprisonment told through the letters of people incarcerated over many centuries, for crimes committed or sometimes even for no reason at all. It is a story that runs from St Paul right up to the present day.

The act of depriving someone of their liberty is one of humankind’s most enduring responses to ‘crime’ through history. What society has sought to achieve over the years by doing so has shifted across the centuries and there is now a variety of purposes: to express disapproval; for the purpose of straight-up punishment through the removal of freedom; to protect the general public; to rehabilitate, perhaps even to forget about those with whom we simply cannot cope.

The letters assembled here come from all parts of the world, and from time immemorial: Thomas Cromwell, Mary Queen of Scots, Éamon De Valera, Al Capone, Martin Luther King Jr and many more.

These letters not only reveal what it is like to be behind bars, but raise issues that are still of pressing interest for us today – such as the death penalty, miscarriages of justice, redemption and social change. They shed light on a system which is primarily one of contradictions – there are letters which inspire, horrify, letters which awe and condemn – even letters which make you laugh or cry.

Available in hardback and e-book formats.

Links to buy

Bloomsbury

Waterstones

Amazon

Bookshop.org

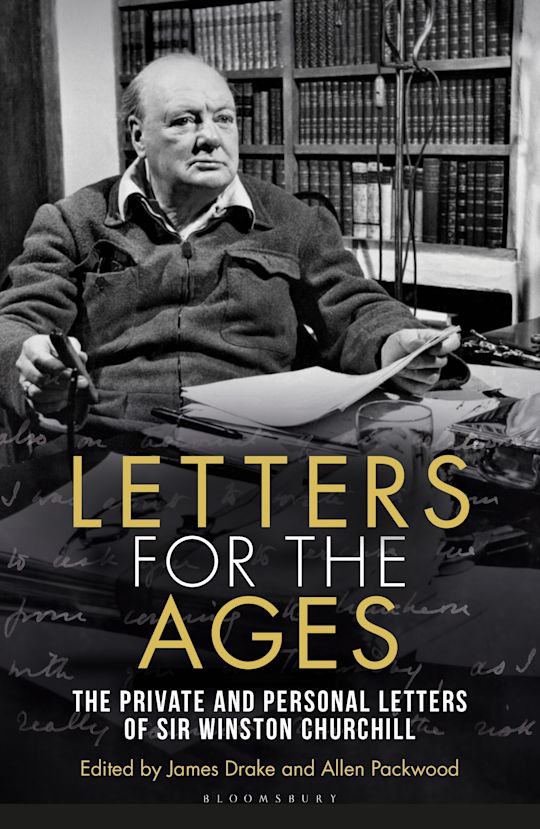

Sir Winston Churchill

Here are some of the best of Churchill’s letters, many of a more personal nature, written to a wide range of people, including his schoolmaster, his American grandmother and former President Eisenhower.

Letters for the Ages concentrates on the more intimate words of Winston Churchill, seeking to show the private man behind the public figure and shine fresh light on Churchill’s character and personality by capturing the drama, immediacy, storms, depressions, passions and challenges of his extraordinary career. These letters take us into his world and allow us to follow the changes in his motivations and beliefs as he navigates his 90 years. There are intimate letters to his parents, his teacher at Harrow, his wife Clementine, Prime Minister Asquith, Anthony Eden, President Roosevelt, Éamon De Valera and Charles De Gaulle.

The letters are presented in chronological order, with a preface to each explaining the context, and they are accompanied throughout by facsimiles of said letters and photographs, offering the reader a sense of Churchill in his most private moments.

Available in paperback, e-book, and audio book formats.

Links to buy

Bloomsbury

Waterstones

Amazon

Bookshop.org

Great Musicians

A collection of letters written through the ages from musicians of all genres, from Mozart to Elton John.

For tens of thousands of years, across various civilisations, our species has been creating music. But what is behind the human fascination with music? This new volume in the Letters for the Ages series explores that question through the personal correspondence of history’s most brilliant musical talent, ranging from Hildegard von Bingen to Amy Winehouse.

Spanning from the 12th to the 21st centuries, the letters assembled in this collection combine to delve into musicians’ personal relationship with music and the creative process behind their greatest works of art. Witness your musical idols, warm-hearted and compassionate, arrogant and angry, insecure and egocentric, defeated and morose.

The letters give a rare insight into the innermost thoughts of these great musicians who have created some of the most recognisable and beautiful music ever heard. But despite the mass of talent within these pages, these letters also provide the realisation that even the most extraordinary music has been created by normal people with everyday worries and preoccupations.

Published 25 September 2025.

Pre-order here: