December is firmly upon us. Time to dig out that garish jumper from the back of the wardrobe, purchase an inordinate amount of tinsel and stock up on stamps ready for the annual Christmas card drop-off at your local post box.

Every year many of us set aside room in our shopping trolleys for packs of beautifully illustrated Christmas cards to be filled with heartfelt messages for our friends and family. Last year, arguably one of the hardest in living memory, over half of Britons stated that sending out Christmas cards was more important than ever.

Perhaps the reason behind this figure is that this particular form of correspondence was designed to spread joy. It allows the writer to reflect on the year that has passed and hope for better things to come.

At Of Lost Time, we simply adore this very merry tradition and so have been scouring various archives to select a handful of poignant Christmas cards from the past.

A New Christmas Tradition (1843)

Though the first ever Christmas card is believed to have been sent to James I of England by the German physician Michael Maier, it was Henry Cole, the 19th-century civil servant and pioneer of the Penny Post, who first formally suggested the mass exchanging of festive correspondence.

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, the idea of sending Christmas cards was the result of Cole’s hectic schedule. Finding himself overwhelmed with letters at the end of the year, he conceived of a method which would allow him to still keep in touch with those he held dear, but in a more manageable way.

Cole asked his friend, the artist John Callcott Horsley, to design for him a lovely Christmas scene to be placed on a card that he could send round to people.

Though created in the Victorian period, Horsley’s image of a family sitting around a table, indulging in a Christmas tipple, will be familiar to many today. Though it is slightly concerning that a little girl has managed to sneak a sip of wine.

It seems though, Cole may have been a bit ahead of his time with this creation. When it hit the market in 1843 (sold for a shilling each) the cards didn’t really take off, perhaps because they were quite expensive for the time.

Still, Cole made an important first step and soon this method of corresponding with people over Christmas would become more affordable and much more popular.

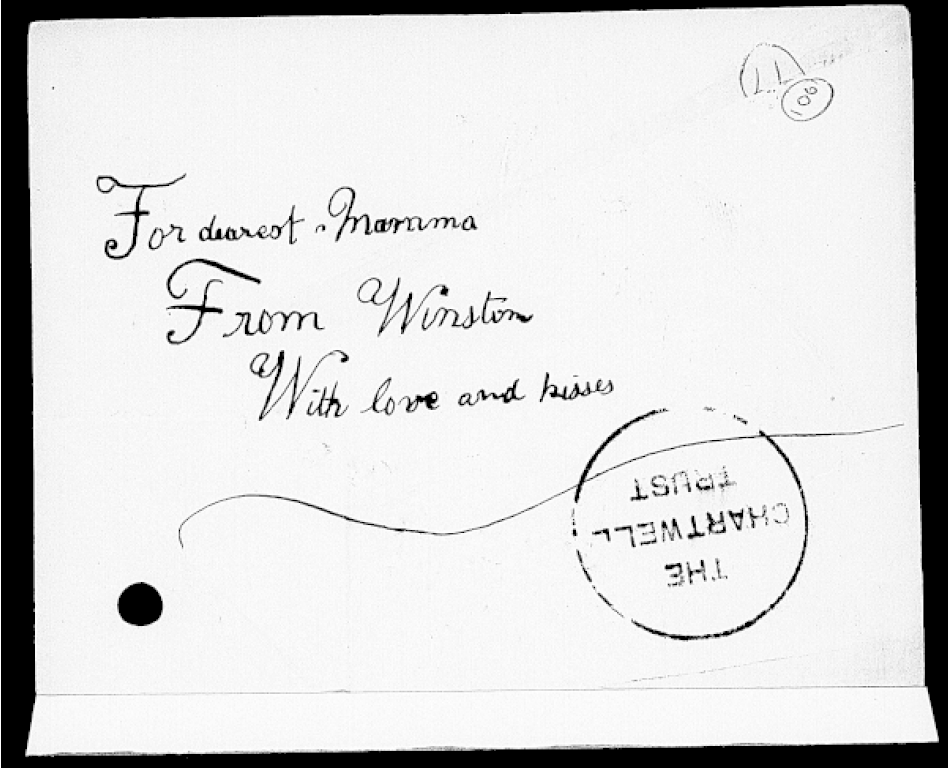

Churchill’s Childhood Christmas Card (1886)

The image of Winston Churchill, puffing on a cigar and sticking two fingers into the air, is so iconic that one can easily forget that, before becoming a behemoth of British politics, he was a young boy who lived away from home and missed his family.

In 1886, a 12-year-old Churchill was boarding at Brunswick School in Hove. He started being schooled away from home at age 7 and was not keen on the process at all. Commenting on his school life, he famously said “I was no more consulted about leaving home than I had been about coming into the world.” The young Chruchill struggled to cope away from his family, in particular his dear Nanny Everest.

He would frequently write home, pleading with his mother and father to come and visit – though his requests often fell on deaf ears. Though the message in this Christmas card is concise, it serves as a reminder. A reminder that, even those figures of the past, who have taken on an almost mythical status, were keen to connect with people they loved at Christmas. Just like all of us.

OLT is currently working with the Churchill Archive to produce a collection of correspondence from Winston Churchill’s life. Look out for updates in the new year!

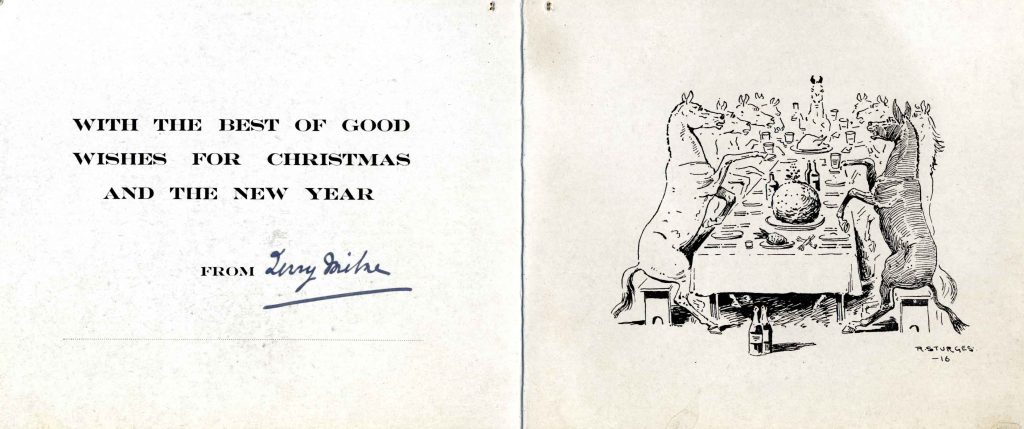

Christmas in the Trenches (1916)

Separated from their families at one of the most special times of the year, Christmas cards offered men battling in Europe with a vital link to home during the First World War.

Thankfully, many of the cards sent survive today in multiple archives so we are able to see the variety of styles that were on offer. For example, York Castle have a large collection which shows humour was a common theme for these cards. A way to distract from the horrors of the trenches.

A particularly striking Christmas card from that collection is pictured to the left. It features a beautiful drawing of a solider, waving to a woman in ‘Blighty’ hoping to go back there in the new year (1917). It’s such a heart-breaking picture given that we know the young men stuck across the Channel would have to wait until the end of 1918 before they could return to their loved ones.

It seems bringing cheer to those back home was of the upmost importance for the person sending this card though, as it features a hilarious sketch of a group of horses settling down to a Christmas dinner. The writer clearly wanted to bring a smile to the face of the person reading it because, as we all can attest, a card from someone you care about has the power to bring a moment of comfort, even in the darkest of times.

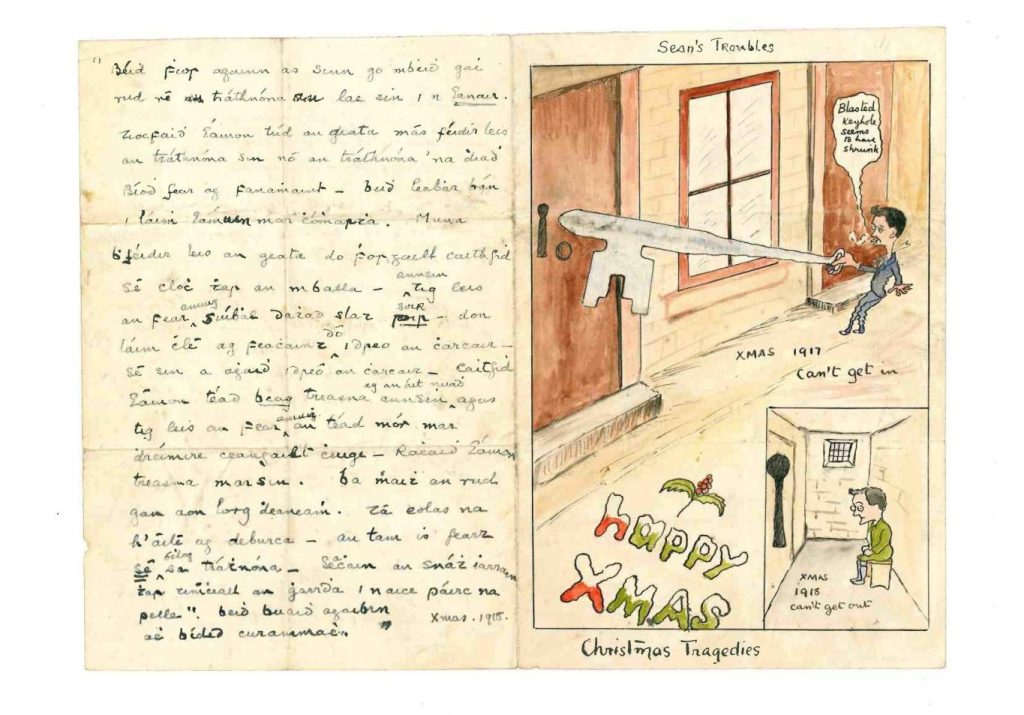

Festive Prison Break (1918)

For most of us, a Christmas card is a way to keep in touch with someone we care about, and perhaps spread a little festive cheer while we’re at it. For Éamon de Valera, a Christmas card was a way of escaping prison.

In 1918, the future Taoiseach, and later President, of Ireland, was accused of collaborating with German forces as part of an anti-British plot. De Valera was arrested, charged and sent to Lincoln Prison to serve his sentence.

He had already spent some time at Lincoln, imprisoned for his role in the Easter Rising of 1916. He was familiar with the prison’s layout, in particular a large backdoor that would make the perfect route for escape. There was just one question: how would he open it?

De Valera hatched a plan. If he could get someone on the outside to make him a copy of the key for the door, they could smuggle it into the prison and he could break free. With Christmas approaching, many inmates would be sending out a card to their loved ones so he could use that to detail his scheme. But correspondence from inmates was closely monitored by guards so he couldn’t just write out his idea, he had to be more creative.

De Valera charged fellow inmate, Sean Mallory, with creating a sketch that would help him flee. The comedic drawing depicts a drunk man, struggling to fit a large key into a lock. What those scrutinising the card did not realise however, was that the key in the picture was an exact match for the one used to lock the door De Valera had eyed for his escape.

The card was sent to his Irish Republican comrades who created a copy of the key that was required. Concealed inside a fruitcake, the key reached De Valera without any issue. There was just one problem: it was too small. Not deterred, De Valera kept repeating his plan until finally he received a key copy which fit the lock perfectly. De Valera finally escaped from prison in February 1919, all thanks to his ingenious use of a Christmas card.

You can read more about De Valera’s time in jail in our upcoming book, Letters for the Ages: Behind Bars (to be released late 2022).

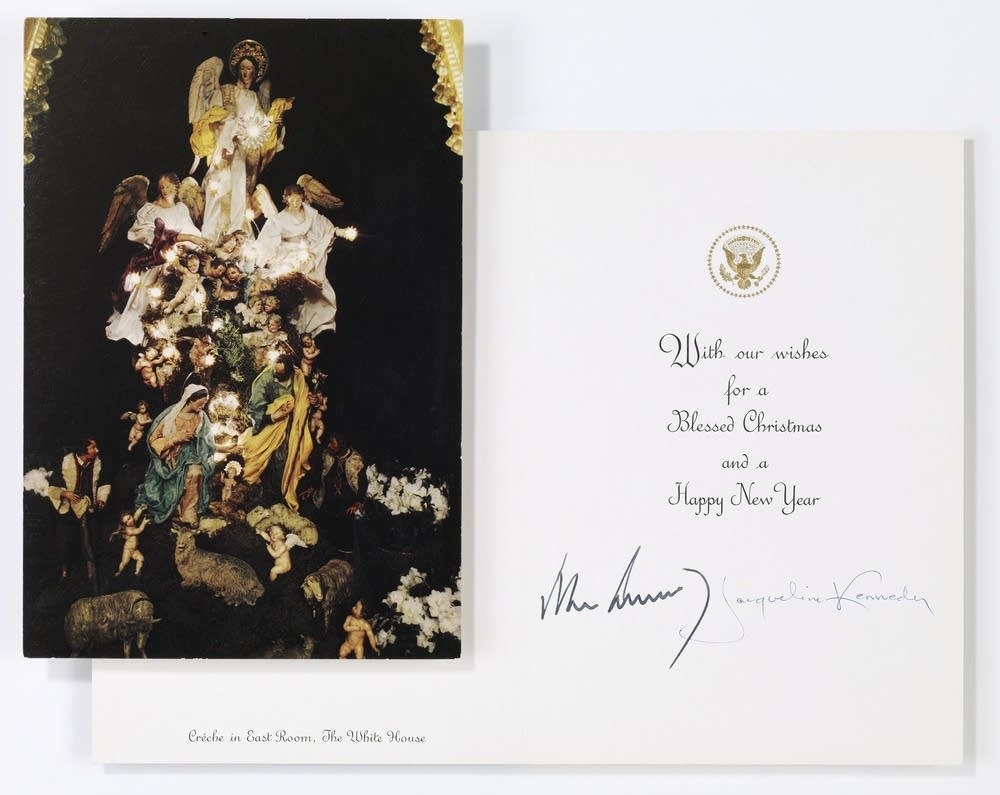

JFK’s Last Christmas Card (1963)

The Christmas of 1963 was supposed to be very different for John and Jacqueline Kennedy. The pair had already started making preparations in November, planning to spend the holidays in Palm Beach, Florida and ordering the official presidential Christmas card to be sent out that year.

The image chosen was a stunning depiction of the Nativity scene, taken from an 18th-century Neapolitan painting that had been hung in the East Room of the White House since 1961. Likely chosen to affirm JFK’s commitment to the Catholic faith, it was to be the first time a religious image would appear on the White House Christmas card.

But the card was never sent, and the couple never made it to Florida. On 22 November 1963, whilst travelling in Dallas with his wife, President John F Kennedy was fatally shot. Jackie would spend that Christmas mourning the loss of her husband, trying to come to terms with the tragic events that had unfolded.

Before embarking on their trip to Texas, John and Jackie did manage to sign a handful of cards, assuming they had much more time to get them finished.

You can watch OLT’s examination of another famous piece of Kennedy correspondence here.