“… the future, the things to come, and intermingling with it, an uneasy sense of a world gone awry”

“Wilderness preservation is a vital part of the solution of this dilemma… giving spiritual solace to urbanised, over-developed man- and woman-kind.”

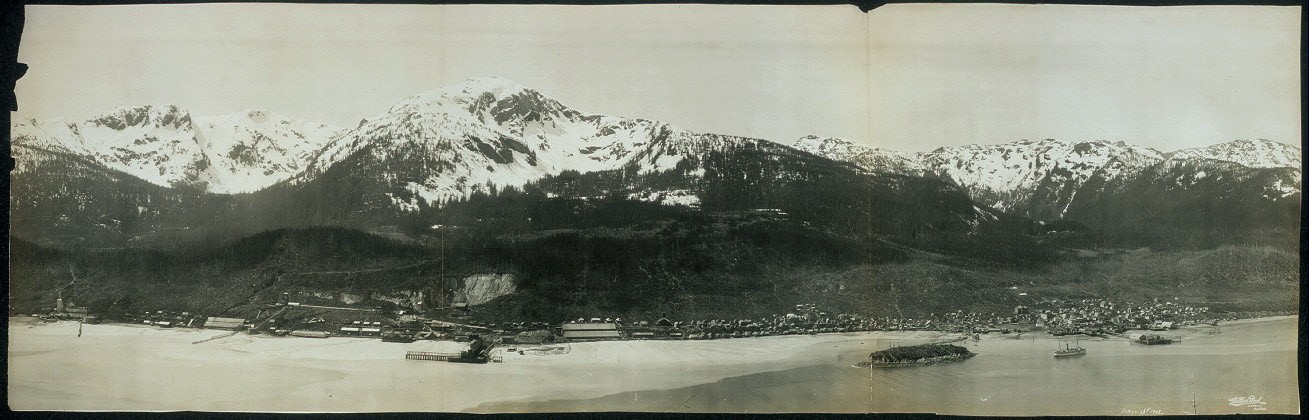

“Already the trans-Alaska oil pipeline and accompanying haul road have bisected the huge block of wilderness which formerly existed north of the Yukon River.”

“The trends noted above can spell the end of wild country… but they need not.”

“Congress can be encourage by citizen supporters to act promptly to protect the wild environments”

“You who read this fifty years hence will understand how well we Americans of the Bicentennial generation have responded to the challenge.”

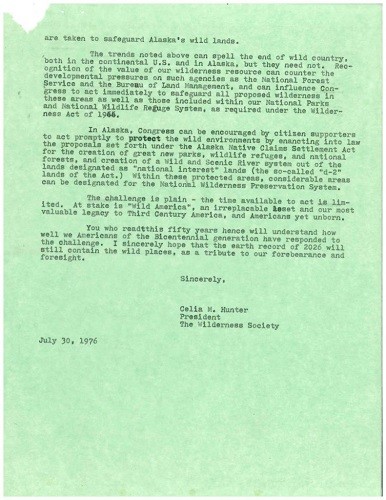

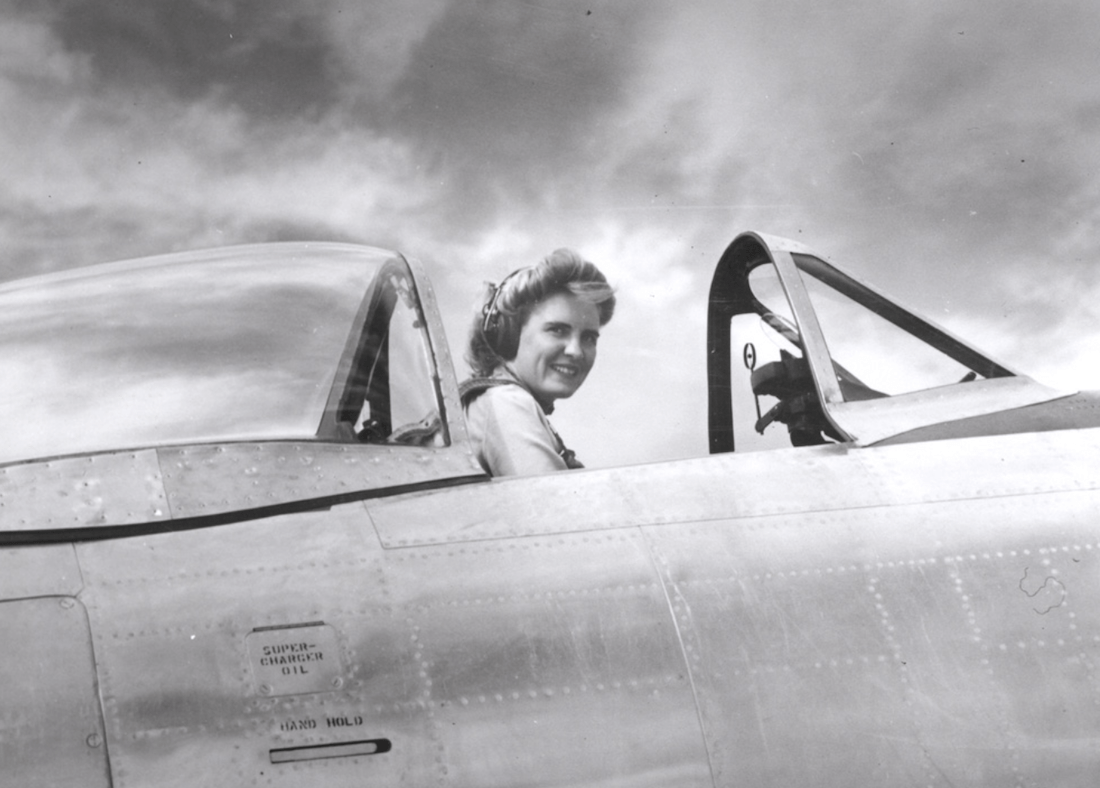

Celia M. Hunter (1919–2001) began her career as a pilot in the Second World War. Alongside her friend Ginny Hill Wood, she flew to Fairbanks in Alaska at the end of the war, a journey that took twenty-seven days of flying. The pilots arrived amid a snowstorm, and were happily stranded for several weeks, which left a remarkable impact on Hunter’s imagination.

She would return five years later for good, setting up a camp for hikers on the boundary of the Denali National Park, and remaining there to the end of her life.

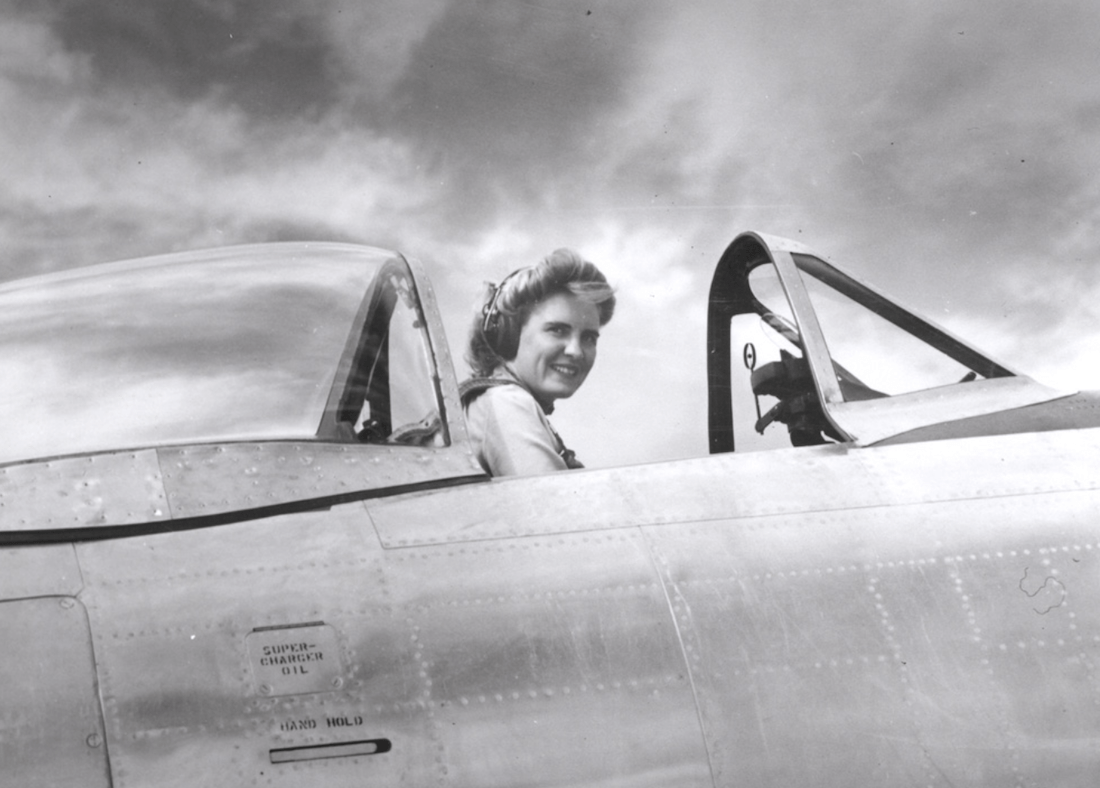

Alaska was considered a military district up until it gained statehood in 1959. That statehood was a double-edged sword: it allowed the central government to select over 100 million acres of land considered “vacant”, but which included land held by First Nation Indians and Aleut people. It also resulted in an influx of settlers, for now Alaska was understood to be a vast resource.

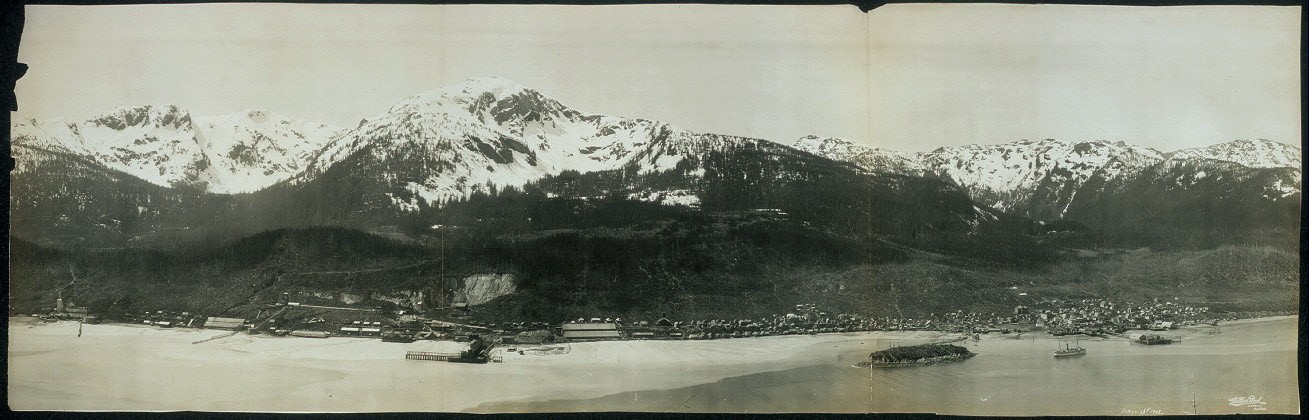

Alaska, Library of Congress

Across the 1950s, Hunter became increasingly active in campaigns to protect the Alaskan wilderness, joining The Wilderness Society, which helped to push through a historic bill that established the Arctic National Wildlife Range in 1960, protecting nearly 9 million acres of land, and halted dam-building on the Yukon River.

But it was not enough. The National Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management continued to extract timber in lands not included by the range, new pioneers kept arriving, each with their own entrepreneurial scheme to profit from the Alaskan land.

In this letter, part of a Bicentennial exhibition at the National Space Agency, Hunter refers to a historic settlement of 1971, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which redressed the moment of statehood and its ensuing land disputes by legally ascribing 44 million acres of land to Native Alaskans; President Nixon’s administration then paid $963 million for control of the rest. For Hunter, a non-native, this settlement did not signify ingenious land rights, but rather a threat to the wilderness.

In her mind, any land not legally made into a refuge was under threat, whether from oil drilling or local hunting.

Alaska pipeline, Library of Congress

By 1980, some of her hopes were realised, when the Arctic Range was expanded and renamed Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, now covering over 19 million acres of land. Hunter was a tireless campaigner and on the night before her death in December 2001 she was up writing a letter to US Congress, to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge from oil drilling.

Campaigning to protect the Alaskan wilderness was among her last acts.