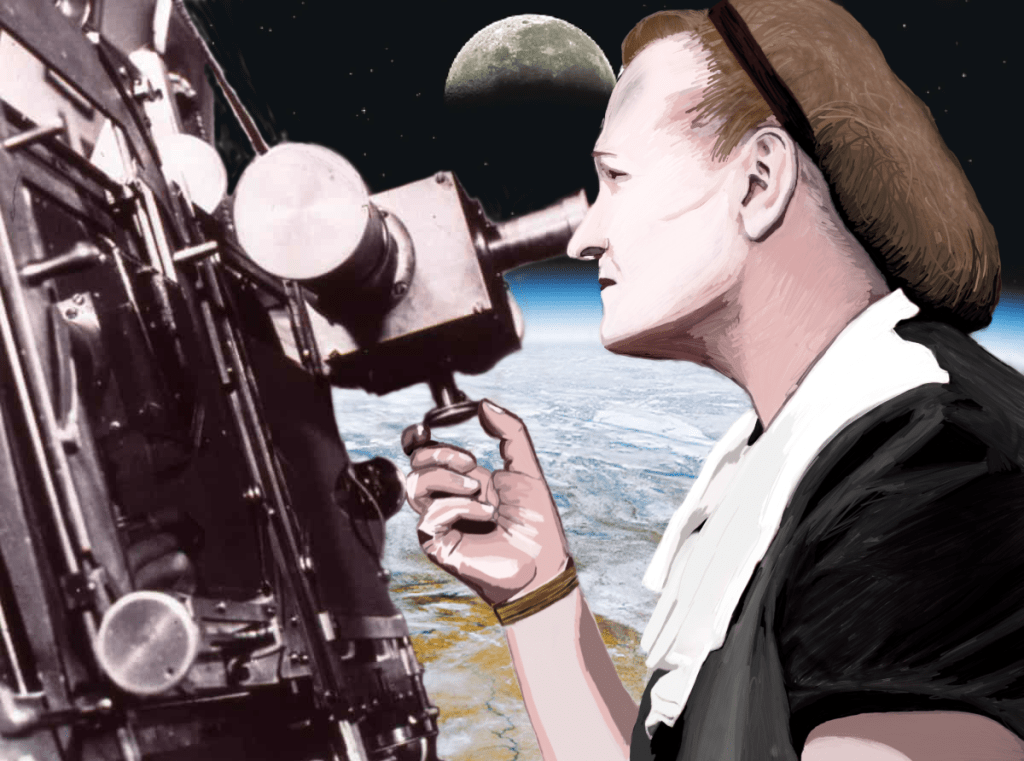

By the time Cecilia Payne peaked through a spectroscope for the first time in 1923, the notion that the elemental constitution of stars replicated the anatomy of our Earth was sacrosanct; a pillar of astronomical understanding. However, it was not long after her birth in 1900, that Cecilia demonstrated the first glimpses of her relentless curiosity and fearlessness to challenge convention. Staring up at the darkened sky at the age of five, her fate became clear; “I was seized with panic at the thought that everything might be found out before I was old enough to begin,” she wrote at the end of her life.

Thwarted from starting her postgraduate studies in England, Payne took to the shores of America, where she became the first person to be awarded a PhD in astronomy from Harvard University, composing what would be described as “undoubtedly the most brilliant PhD thesis ever written in astronomy” (Otto Struve). In it, she unravelled the link between the spectra of stars and their temperatures, demonstrating that the most dominant element in the atmosphere was in fact the lightest: hydrogen. Everything astronomers had thought they had known up until that point was refuted, no less, by a woman.

Following her discovery, her external advisor Henry Norris Russell at Princeton University wrote to dismiss her observations:

“January 14, 1925

My Dear Miss Payne:

…

You have some very striking results which appear to me, in general, to be remarkably consistent. Several of the apparent discrepancies can be easily cleared up. […]

There remains one very much more serious discrepancy, namely, that for hydrogen, helium and oxygen. Here I am convinced that there is something seriously wrong with the present theory. It is clearly impossible that hydrogen should be a million times more abundant than the metals […]

Very sincerely yours,

Henry Norris Russell”

Owing to her controversial role as a woman in science, Payne would be forced to keep and low profile and persistently tolerate low pay. Yet, in 1929 Russell published his own findings, the results of which replicated those he had dismissed four years prior. Payne would never be credited for her original brainchild.

Characteristic of the thinking of the time, Abbott Lawrence Lowell (President of Harvard, 1909-1933) asserted that ‘Miss Payne should never have a position in the university as long as he was alive.’ However, the stars aligned in her favour. He was soon replaced, leading her to become the first woman to attain a professorship at Harvard.

Almost a century later, today her portrait decorates the illustrious surroundings of Harvard’s University Hall, no more than 30ft from that of Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the man who doubted her future. Such is the beautiful irony, which Payne would no doubt have appreciated.

https://harvardpress.typepad.com/hup_publicity/2020/02/the-most-famous-astronomer-youve-never-heard-of.html